19 February 2026 – Beyond the Budget Series

Brian Cronin, Economist

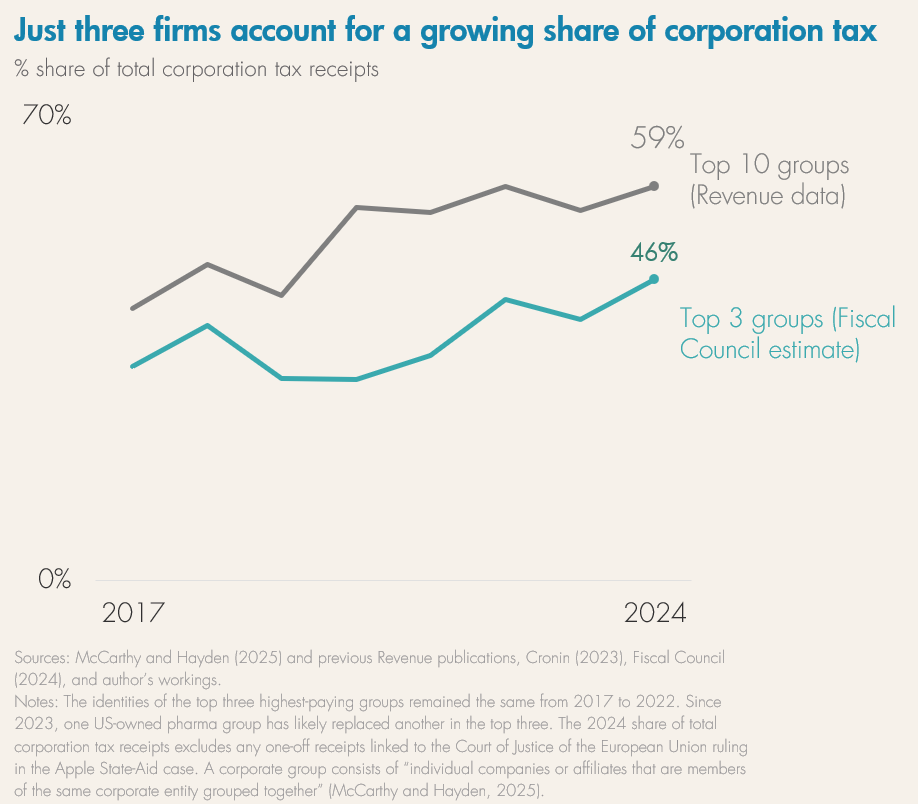

Ireland’s corporation tax revenues are exceptionally concentrated. This is well-documented. But the growing reliance on a very, very small number of multinationals is less well-known. Our estimates suggest that this reliance grew even further in 2024.

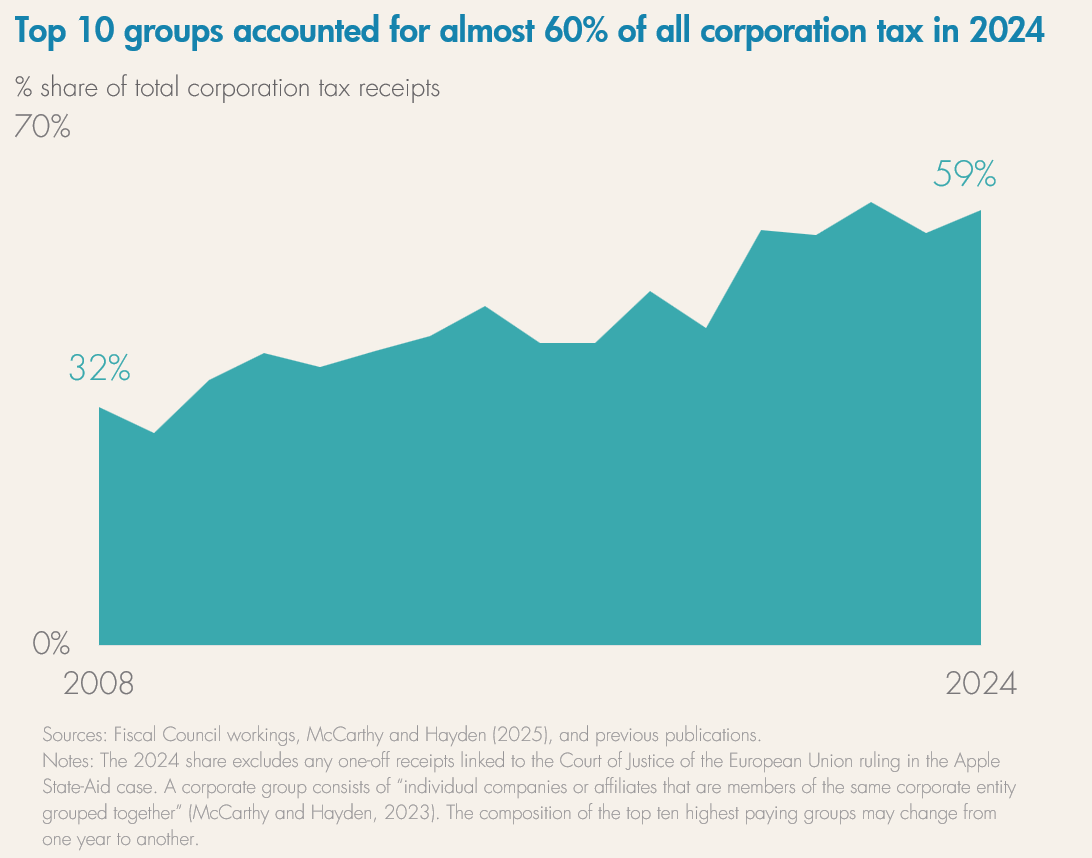

Official data shows that the top ten highest paying corporate groups accounted for almost 60% of total corporation tax receipts in 2024, up from around a third in 2008.1

When thinking of concentration risks, it is important to consider whether the top ten companies vary over time. If the same companies remain in the top ten each year, and they account for the bulk of corporation tax payments, the concentration risk is higher.

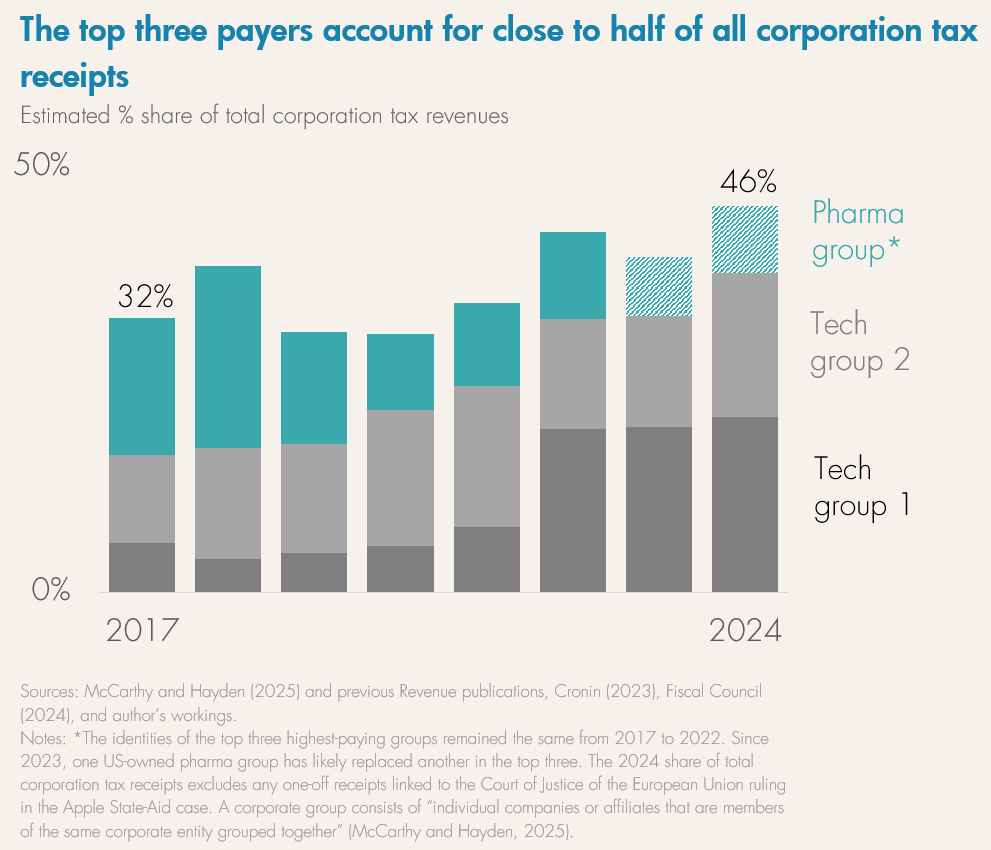

Cronin (2023) estimated the top three highest paying corporate groups accounted for, on average, around a third of all corporation tax revenues from 2017 to 2021. Using the same approach, the Fiscal Council estimated that these revenues were even more concentrated in 2022. The identities of these three groups did not change during this time.

Since 2023, the composition of the top three has likely changed.2 Two tech companies have remained in the top three every year since 2017. However, one of the previous top three, a pharma group, has seen its profits fall sharply in recent years. As a result, it appears to have paid less corporation tax in Ireland.

It was likely replaced in 2023 by another US-owned pharma group. This was the first change in the top three since 2017. The identities of the top three remained the same in 2024 and are likely to have stayed unchanged in 2025.

Since 2022, two key developments have occurred.

First, the corporation tax paid by two of the biggest payers has increased substantially. Both of these companies are in the tech sector. We estimate that these two groups paid almost €11 billion of corporation tax in Ireland in 2024, equivalent to almost 40% of total corporation tax receipts.

Second, Ireland’s corporation tax revenues have become even more concentrated. In 2024, we estimate the top three highest paying corporate groups accounted for 46% of all corporation tax revenues, roughly €13 billion. Corporation tax almost doubled between 2021 and 2024.3 This was largely driven by increased payments from the top three payers.

Greater concentration means greater uncertainty

As corporation tax revenues become more concentrated, they also become more risky. That is, Irish tax revenues are more exposed to the fortunes of specific firms and the decisions they make. This raises the uncertainty around future receipts and the risks that they could be much higher or lower than current levels.

On the upside, the two highest paying tech companies continue to perform strongly. They each reported double-digit global revenue growth in 2025. And market analysts expect this growth to continue into 2026 at least, supported by strong demand for their latest products and services.

In addition, Ireland appears to be a key manufacturing base for the active ingredient used to make hugely popular weight-loss and diabetes medicines (Cronin, 2025b). Higher sales of these medicines in 2025 increased corporation tax receipts in Ireland. Some of this was because one large pharma group frontloaded some exports to the US ahead of expected tariffs. But it appears there has been a permanent increase in production in Ireland. It is not yet clear how big this long-term increase in exports will be. These medicines are extremely profitable, and their sales are forecast to grow significantly.

Beyond strong underlying demand, pharma sector profits may also be boosted by new blockbuster drug approvals, expanded uses for existing drugs, and possible price increases in non-US markets.

Finally, the 15% minimum effective tax rate for large corporations will lead to increased corporation tax from 2026 onward. Previous estimates (Cronin, 2025a) suggest this higher tax rate could yield an additional €5 billion in corporation tax receipts.4

However, there are also clear downside risks.

Relying heavily on just two of the world’s biggest tech companies for a substantial stream of corporation tax revenue carries significant risks. At the firm or the sector level, developments such as new products not selling well, senior leadership change, pivots to new product forms, and tighter regulation of the industry could result in a sharp fall in profits.

In addition, the biggest tech firms continue to invest heavily in artificial intelligence, hoping this will generate large profits in the future. However, it remains unclear whether these lofty profit expectations will be realised (IMF, 2025). As a result, the range of possible outcomes for future tech sector profits, and by extension the corporation tax that these firms pay, is very wide and highly uncertain.

For the pharma sector, a key risk is drug prices. There are policies in motion in the US to reduce prescription drug prices. If the sale price of branded drugs in the US falls, then the profits of the firms that make them would also fall, all else equal. Tariffs on pharmaceutical products could also reduce profitability in the sector. However, this appears less likely, as most major firms have already made bilateral arrangements with the Trump administration.5

Lastly, while the largest corporation tax payers in Ireland have bases that are well established here, their group structures are sensitive to the global landscape. Further changes in tax, trade and industrial policy in the US could make a big difference to their location decisions.

Ireland’s corporation tax receipts have benefitted significantly from changes to international tax systems in the past (Cronin, 2025a). There is a risk future policy shifts reverse at least some of those gains. This argues for saving a larger share of corporation tax than the 13% that the Government currently plans to over 2026–2030.

The opinions expressed and arguments employed in these blogs do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Fiscal Council.

Footnotes

- The 2024 share excludes any one-off receipts linked to the Court of Justice of the European Union ruling in the Apple State-Aid case. The Revenue Commissioners note that the composition of the top ten groups may change from one year to another. ↩︎

- These are Fiscal Council estimates. Cronin (2023) discusses the limitations of this analysis. Our estimates are, by necessity, much cruder than we would like. However, we are left with no alternative, given the absence of publicly available subsidiary-level information and the very strong likelihood that these groups are among Ireland’s largest corporation taxpayers. ↩︎

- This is even when we exclude one-off receipts linked to the Court of Justice of the European Union ruling in the Apple State-Aid case in 2024. ↩︎

- This increase would be spread over 2026 and 2027. ↩︎

- While exact details remain confidential, reports suggest the agreements include commitments by the companies to reduce prices on certain prescription drugs and boost investment in the US. In return, the US Government will defer Section 232 tariffs on imported drugs for three years. ↩︎